Modern technology uncovers Mancetter's 2,000-year-old secret on Boudica's last battle location

By Nick Hudson 3rd Jun 2020

AREA HAS WHAT LATIN SCHOLARS CALLED VENDITIONIS PUNCTUM UNIQUE – A USP WHICH MAKES IT STAND OUT IN A CROWDED FIELD OF COMPETITIORS

AND ATHERSTONE CIVIC SOCIETY SECRETARY MARGARET HUGHES BELIEVES HISTORY SPEAKS TO US WITH A 'FORKED TONGUE'

REGULAR readers will recall the previous instalments of Margaret Hughes's series about Mancetter's claim to be the site of Queen Boudica's last stand against the Romans which could have changed the course of our island narrative over the next 2,000 years.

Nub News has decided to pick a fight with British history and join the Atherstone Civic Society secretary's quest in a male-dominated field to prove conclusively the staging of the most important battle before Hastings.

In the first she explained why Mancetter's old Roman name Manduessedum is extremely important, because its meaning has to do with Celtic battle.

The name is completely unlike those of the other sites claiming the Boudican battle.

Her second article gave reasons for Boudica and the Romans coming together in the Midlands.

But it didn't yet explain why Mancetter must be that Midlands site.

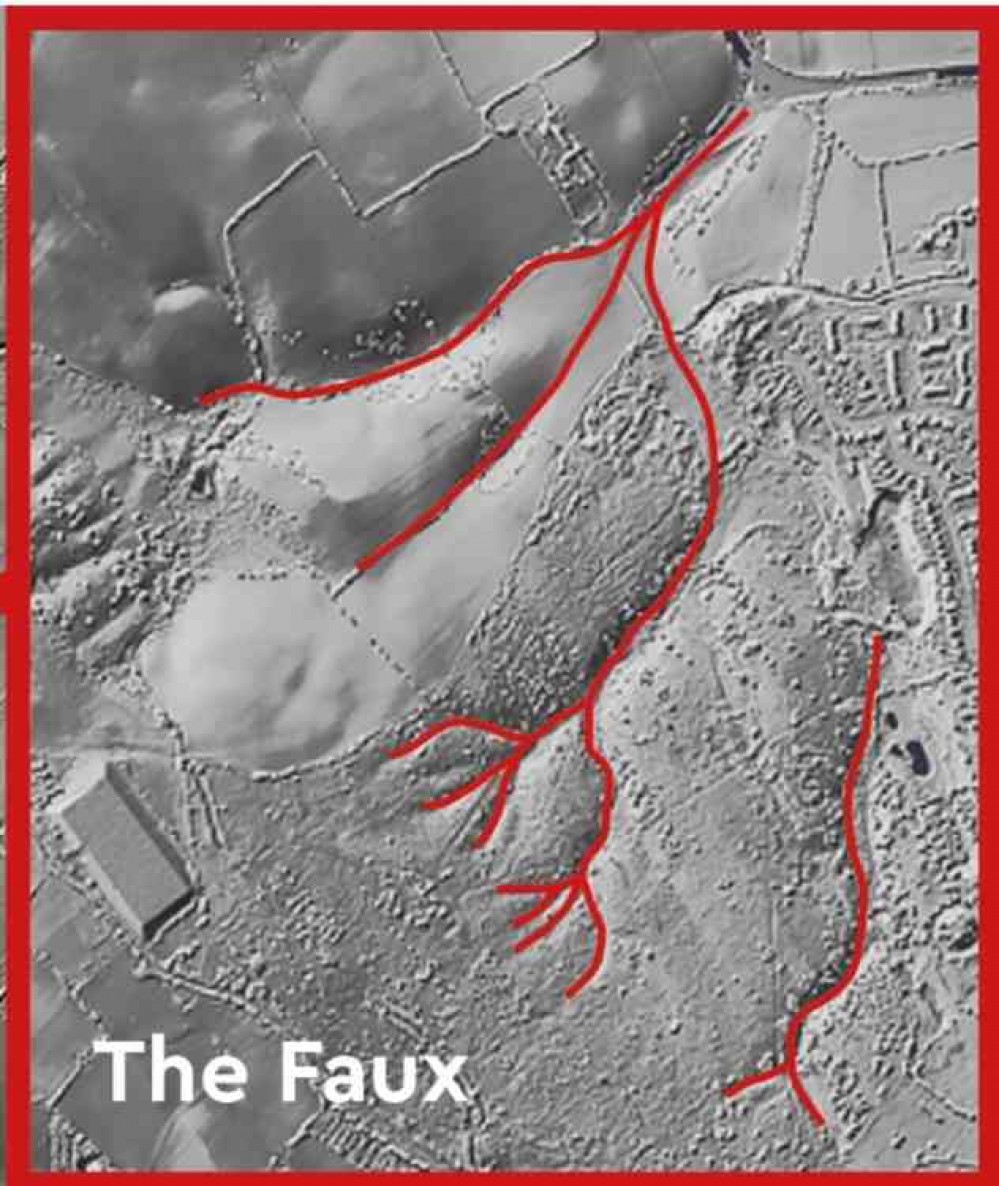

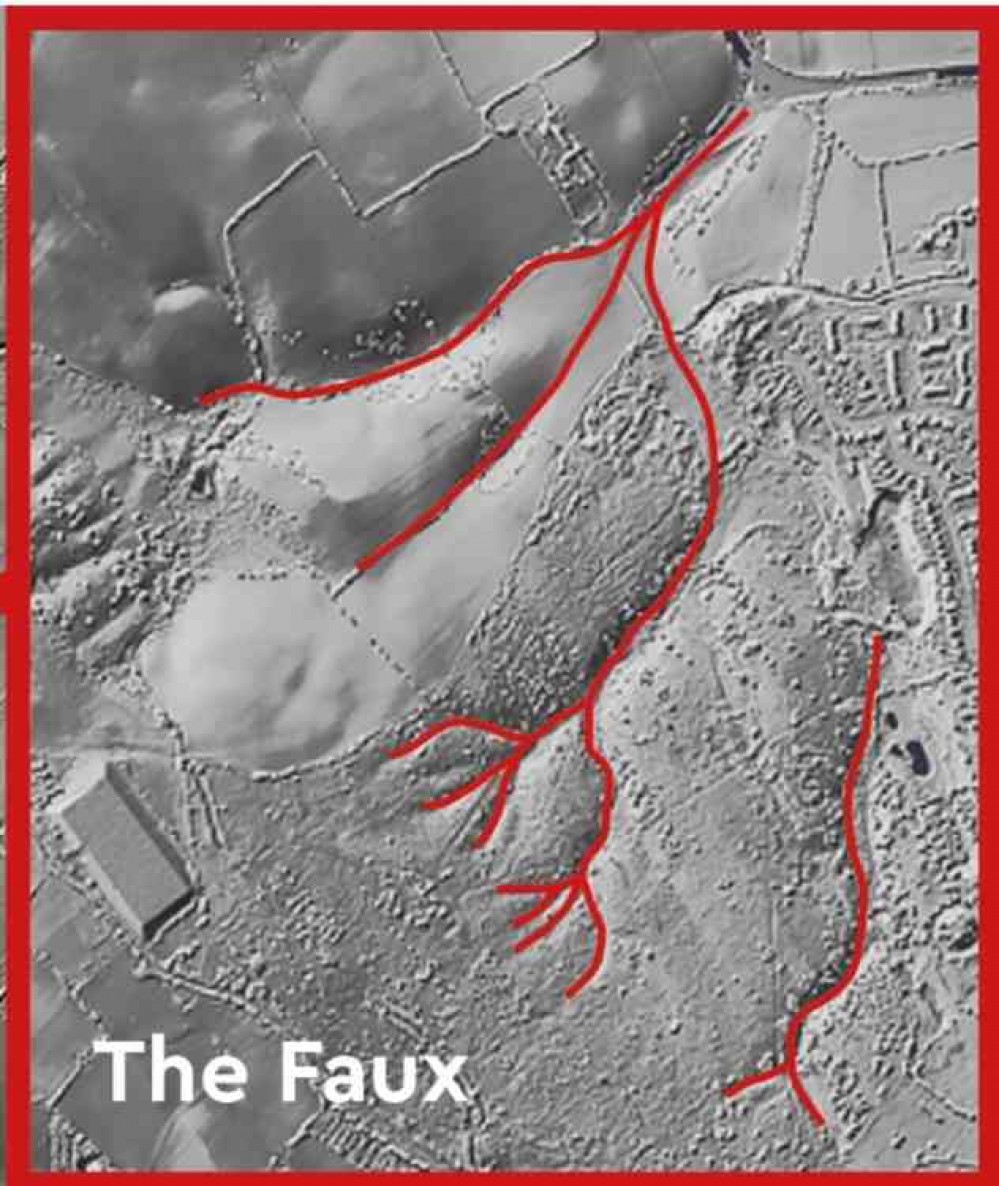

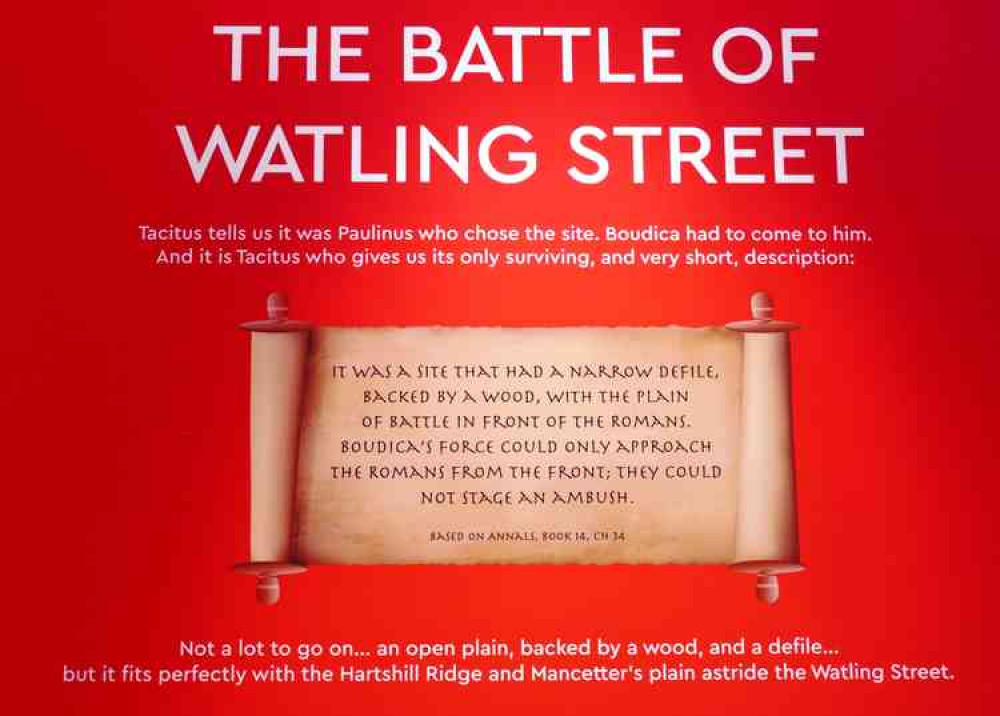

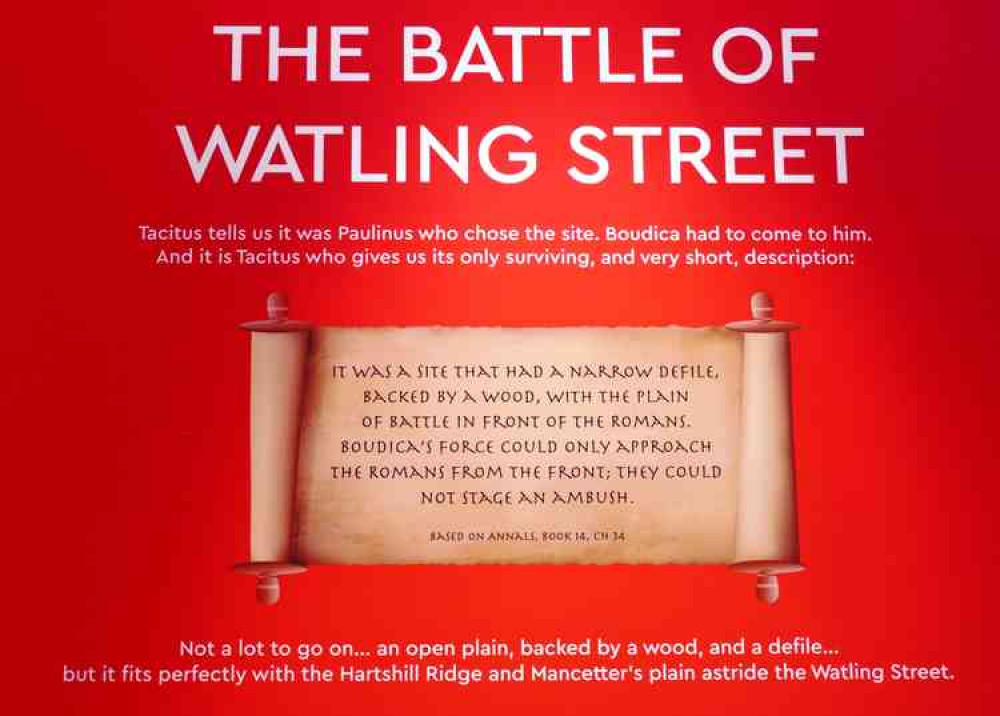

Here she does explain just that. Be prepared for something new and surprising that makes Mancetter's claim distinctive. In my book Boudica At Mancetter I allow ten other historians to put forward suggestions in their own words as to possible sites for Boudica's last battle. That might seem generous – dangerous even, a weakening of the Mancetter argument. But actually I want to open up the debate to let people judge for themselves why Mancetter's claim is so distinctive. Because I have come to see that Mancetter has an outstanding USP, or "Unique Selling Point". It has that particular "something" which alone makes a competitor stand out from the rest. In this quite crowded slate of battle-site candidates, I'm proposing Mancetter is exceptional. I'll sum up the Mancetter USP at the end, but first let me take you through the exciting search that led to its discovery. Back in 2012, as part of a civic society project on Mancetter's Roman history, I was involved in setting up a conference at the University of Warwick. We wanted to showcase debate between eight historians interested in the Boudican battlefield. So theories were thrashed out, everyone given chance to try them out against each other, including an idea that had been in the air since the early 60s: that it's Mancetter that might be THE place. It was while recruiting those debaters that I began to look more carefully into what the history books had to say on the point. I took to trawling through translations of the earliest record of the battle that we have. And that was where, for me, the trail of surprises began. First there was the surprise of finding just how varied these translations are. There's one particular feature of the battle-field that seems to stand out as very important, yet translator after translator gives it their own twist. The word we have to focus on for this landmark is fauces. This Latin word seems to have teased the brain of every historian who's tackled it. It's as though over the centuries people have wrestled with different choices, along the lines of cleft, or gorge, gulley, ravine, canyon, valley, defile – make your choice – and rendered it in various ways. So we've had a "narrow defile", we've had "a spot narrow at the entrance", we've had "a narrow valley", and more. If you try sketching from all these, the resulting pictures are a mish-mash of unhelpfully different things. That's because they all rely on that original, rather tricky Latin term. It seems to leave a lot of room for interpretation. I could see that one secure meaning was needed, based on a fresh translation. I was keen to work on it. I began to research the meaning of fauces. So then, next: the "ah-ha" moment! I stumbled upon a surprise which gave me great delight. Fauces turns out to be a real oddity of a word, a word in a special class. Although it is a single thing...... at the same time it's plural. It's in the same class as "scissors" or "trousers"; that's to say, it's one single item which is forked, or split. It might even be multiply-forked, a shape with branches that fork again and again. So think of the implications of that. When we go searching for a place that fits that early description of the battle-site, we mustn't go looking for a straightforward valley, we have to go looking for a "valley" that splits in two, or forks, and maybe forks again. I felt I had to delve more. I went looking back through classical writings for examples of this unusual word in use, and more surprises tumbled out. Because then it became clear that it's quite a rare word, not for use in any old everyday conversation about valleys. It gets used architecturally to describe a corridor or an entrance. It gets used to describe landscape spaces that are pipe-shaped, or gullet-shaped, or like a cove with a narrow entrance, or the crater of a volcano. Modern words have come from it, such as "faucet". And it crops up in modern anatomy, to describe the gullet, and in botany to describe sepals springing up between petals. However, from all this digging around for the finer meanings, what matters is that we seem to have lighted on the shape of the "valley" or "defile" which played a major part in the battle. We seem to have arrived at a distinctive meaning based on a fresh translation. So now, armed with these shades of meaning, I was ready to move on from a theoretical idea of a valley into the thrill of the reality. So now take a look at what lies within the Hartshill Ridge. It truly is a thrill. Today's technology, in this case LIDAR, exposes beautifully the reality of one particular fauces that etches into the slopes of Hartshill Ridge, above the flat land through which today pass canal, and railway, and the A5, and on which now sits Dobbies. LIDAR's imaging system is similar to radar but with laser light in place of radio waves, and it depicts shapes and dips in the land. It captures from above an almost three-dimensional view of the land below. Here the "fauces" in the Hartshill Ridge has been outlined in red. for clarity. It is shaped like an upside-down capital letter Y, in which the two main branches of the Y split off into further smaller defiles. The prongs of this forked shape almost appear to be so far split as to have virtually fringed ends. Or it could be described as a resembling something almost like a trident. An out-lying branch can be seen off to the east (right). The book Boudica At Mancetter shows this reduced image in a wider background. So, dear readers, what happens next? This Mancetter search should go on. The very fact that now we know about the fauces seems to demand further research. In a future article in this series I'll address the question of archaeology, and the need for further exploration. Perhaps it could start with landscape archaeology – confirmation of the defile's age, modelling of its conditions in AD 60. But for now, let's return to the notion of a USP. Consider: Is there any other competing Boudican site that offers such a compelling match between ancient Roman description and lie of the land? To come closer to the battle, has LIDAR captured for Mancetter a place where Roman legions could have waited, hidden, for the oncoming British opposition? THE MANCETTER USPHere in summary is the unique core of Mancetter's claim to the Boudican battle site:-

• Fresh translation from the earliest record of the battle matches an amazing feature newly-revealed in the Hartshill Ridge. The next "Nub" instalment of the Boudican saga will describe the opportunities that the fauces in the Hartshill Ridge would provide for the tactics the Romans could have used. The classical Roman history mentioned in this article is Tacitus's Annals. That, and further details from this article are dealt with more carefully in the Atherstone Civic Society's publication Boudica At Mancetter, by Margaret Hughes, available from [email protected] . When present circumstances change it will also be available at the new Roman Mancetter & Boudica Heritage Centre at St Peter's Church, Mancetter, also at The Coffee Shop, 2A Church St., Atherstone Footnote: Follow Margaret Hughes in future weeks for more information on the Mancetter battle site claim. Watch out for hopes for further research. If you are interested in being involved, contact Margaret Hughes at Atherstone Civic Society, via [email protected]

CHECK OUT OUR Jobs Section HERE!

atherstone vacancies updated hourly!

Click here to see more: atherstone jobs

Share: